Part 5: Understanding Relative Risk and Absolute Risk…Relatively Speaking, It’s Absolutely Crazy!

A Little Knowledge Lights The Way

Authors:

Kimberly Zambito, MD, Orthopaedic Surgeon and Owner of Qualis Os

www.qualisos.com

Nick Birch FRCS (Orth), Consultant Spine and Bone Health Specialist and owner of OsteoscanUK

www.osteoscanuk.com

Welcome to Part 5 in our series of databases and statistics. In keeping with the Star Wars theme from Part 4 (the fourth is with you). You are about to enter the final stage of Jedi training. Please review Part 4 before beginning Part 5.

Having discussed relative risk as a ratio in comparison to the odds ratio in Part 4, we now need to turn to the very heart of this matter: What are Absolute and Relative Risks and how are they important in judging whether treatment is effective?

Absolute and Relative Risk

Like risk and odds, absolute and relative risk sound similar but are not the same. To begin with we should define the terms:

Absolute Risk (AR) is the actual probability or chance of an event occurring in any defined population over a specific time period. It tells you how likely an outcome is and can be thought of as the baseline likelihood.

Relative Risk (RR) compares the risk of a certain event occurring in two groups. It tells you how much more (or less) likely the event is in one group compared to another. It is therefore the proportional difference between groups. We have already seen one example in Part 4 of our series.

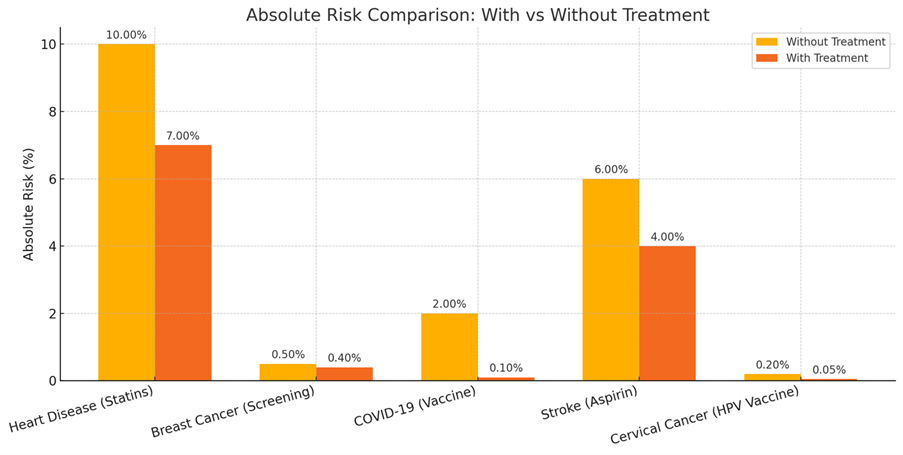

Here are five medical examples that demonstrate the difference between absolute and relative risk.

Heart Disease and Statins

The 10-year risk of a heart attack for a group of individuals could be 10% without statins. With statins the risk might drop to 7%. This represents an absolute risk reduction of heart attacks of 3% but a relative risk reduction of 30%.

Breast Cancer Screening

Without screening, 5 in 1,000 women die of breast cancer over 10 years. With screening, 4 in 1,000 die. The absolute risk reduction is 0.1% (1 in 1000), but the relative risk reduction is 20% (1 fewer death per 5).

Covid-19 Vaccine

In unvaccinated people, the risk of hospitalization might be 2%. In vaccinated people it may be 0.1%. The absolute risk reduction is 1.9%, but the relative risk reduction is 95%.

Aspirin for Stroke Prevention

In high-risk patients, the stroke rate could be 6% without aspirin, but with aspirin 4%. This represents an absolute risk reduction of 2%, but a relative risk reduction of 33%.

HPV vaccination to prevent cervical cancer

The cervical cancer risk in unvaccinated women may be 0.2%. In vaccinated women it could fall to 0.05%. The absolute risk reduction is therefore 0.15% and the relative risk reduction is 75%.

Here’s a chart showing the absolute risk for each medical scenario, comparing outcomes with and without treatment or intervention. This helps illustrate the actual risk reduction patients might experience.

The distinction between absolute risk and relative risk is really important when reviewing research on a clinical trial of an intervention as we want to understand if the intervention is clinically relevant. For example, will taking a medication decrease risk of fracture? Let’s return to Arizona and the Grand Canyon adventures.

In our example (from Part 4), the risk of sustaining a hip fracture while on an adventure in the Grand Canyon is 22.5%. Now, let’s make a change so all participants no matter the chosen adventure are wrapped in bubble wrap. Wrapping participants in bubble wrap decreases the risk of sustaining a hip fracture to 10%.

The absolute risk reduction (ARR) is the risk of something happening minus something happening with an intervention. In this example, ARR is 22.5% - 10%, or 12.5%. This means that if a participant does 100 adventures, 12.5 hip fractures will be prevented by using bubble wrap. Another way to think about it, a participant would have to be wrapped in bubble wrap 12.5 times to prevent 1 hip fracture while doing an adventure in the Grand Canyon. This is referred to as Number Needed to Treat (NNT) which we’ll come back to below. ARR is interpreted in the context of baseline risk.

Relative Risk Reduction is the probability of something happening in one group compared to another group. RRR is an estimate of the percentage risk that is removed because of a new intervention. For example, we have 100 people with flabby muscles. Fifty of these people get treated with a new drug called “pump-you-up” and 1 person falls and sustains a hip fracture. The risk of hip fracture in this group is 1/50, or 2%. The other 50 people do not get the new drug and 2 people fall and sustain a hip fracture. The risk of hip fracture in this group is 2/50, or 4%. In this example, the relative risk is 2%/4%, or 0.5.

If you recall, if RR <1, then risk has been reduced. If RR equals 1, then risk has not changed. If RR >1, then risk has increased.

Things are going to get tricky now. Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) shows how much the risk changes proportionally between the two groups. In our example, the group that received “pump you up” sustained a hip fracture 50% less often than the group that did not receive “pump you up”. This is calculated as control group minus treatment group. This difference is then divided by the control group. In our example, calculation of RRR is as follows (4-2)/4, or 2/4 which is 50%. Advertising for “pump you up” may state “pump you up” decreased hip fracture by 50%. Sounds great!

Not so fast…the Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) is the difference between 2% and 4%. ARR is 2%, meaning use of “pump you up” decreases hip fracture risk by 2%.

Which one of these seems more impressive- RRR or ARR? Many pharmaceutical companies advertise RRR. You are more likely to want to take “pump you up” to prevent hip fractures if risk decreases by 50% rather than 2%. Each is mathematically correct, but RRR seems better than ARR.

Absolute risk gives us perspective on how much benefit a patient is likely to have from a particular treatment or intervention. Relative risk help identify disparities in outcomes. Medical professionals may overestimate the efficacy of a treatment when results are framed in relative risk, rather than absolute risk. ARR considers baseline risk and is a more useful measure than RRR to express efficacy of a particular treatment.

Let’s go back to Number Needed to Treat (NNT) as this reflects the real world of medical treatment. NNT is the number of people who need to receive a treatment for one person to benefit (e.g., avoid an event such as a heart attack or death).

The formula to calculate NNT is: NNT = 1 / Absolute risk reduction (ARR)

Where: ARR = Absolute Risk (control group) − Absolute Risk (treatment group)

So NNT is based on absolute risk, not relative risk. Even if relative risk reduction sounds impressive (e.g. 50% for “pump you up”), the NNT could be high if the baseline (absolute) risk is low.

Low absolute risk = higher NNT (less efficient treatment)

High absolute risk = lower NNT (more efficient treatment)

NNT is a very patient-centric measure and is one of the best ways to look at a treatment if you want to know whether it is likely to benefit you.

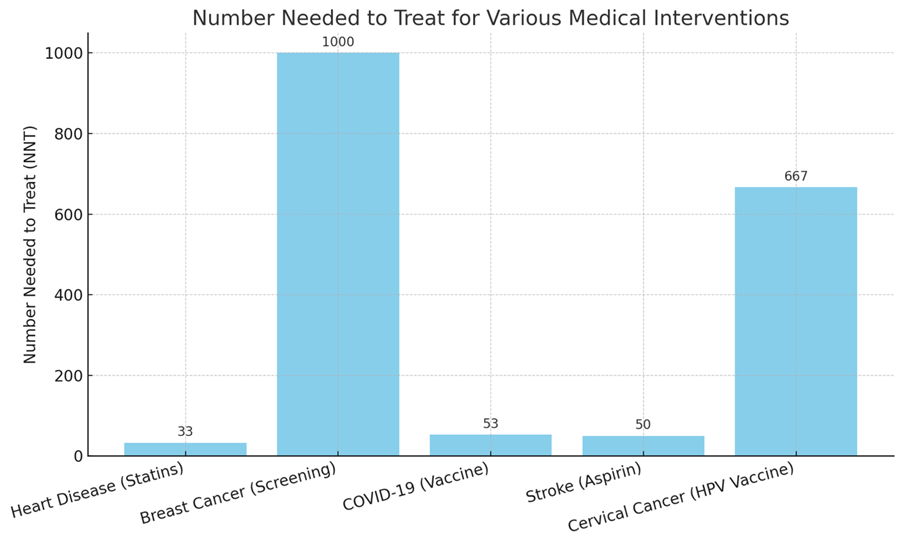

Returning to the five medical examples we looked at earlier, the NNTs are:

Condition Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) NNT

Heart Disease (Statins) 3.0% 33

Breast Cancer (Screening) 0.1% 1000

COVID-19 (Vaccine) 1.9% 53

Stroke (Aspirin) 2.0% 50

Cervical Cancer (HPV Vaccine) 0.15% 667

A lower NNT means the treatment is more effective in preventing one adverse event. A higher NNT still might be acceptable if the intervention is low-risk, low-cost, or applied to large populations, such as breast cancer screening.

Here’s a chart showing the Number Needed to Treat (NNT) for each medical example. Lower bars indicate more effective interventions in terms of how many people need to be treated to prevent one adverse outcome.

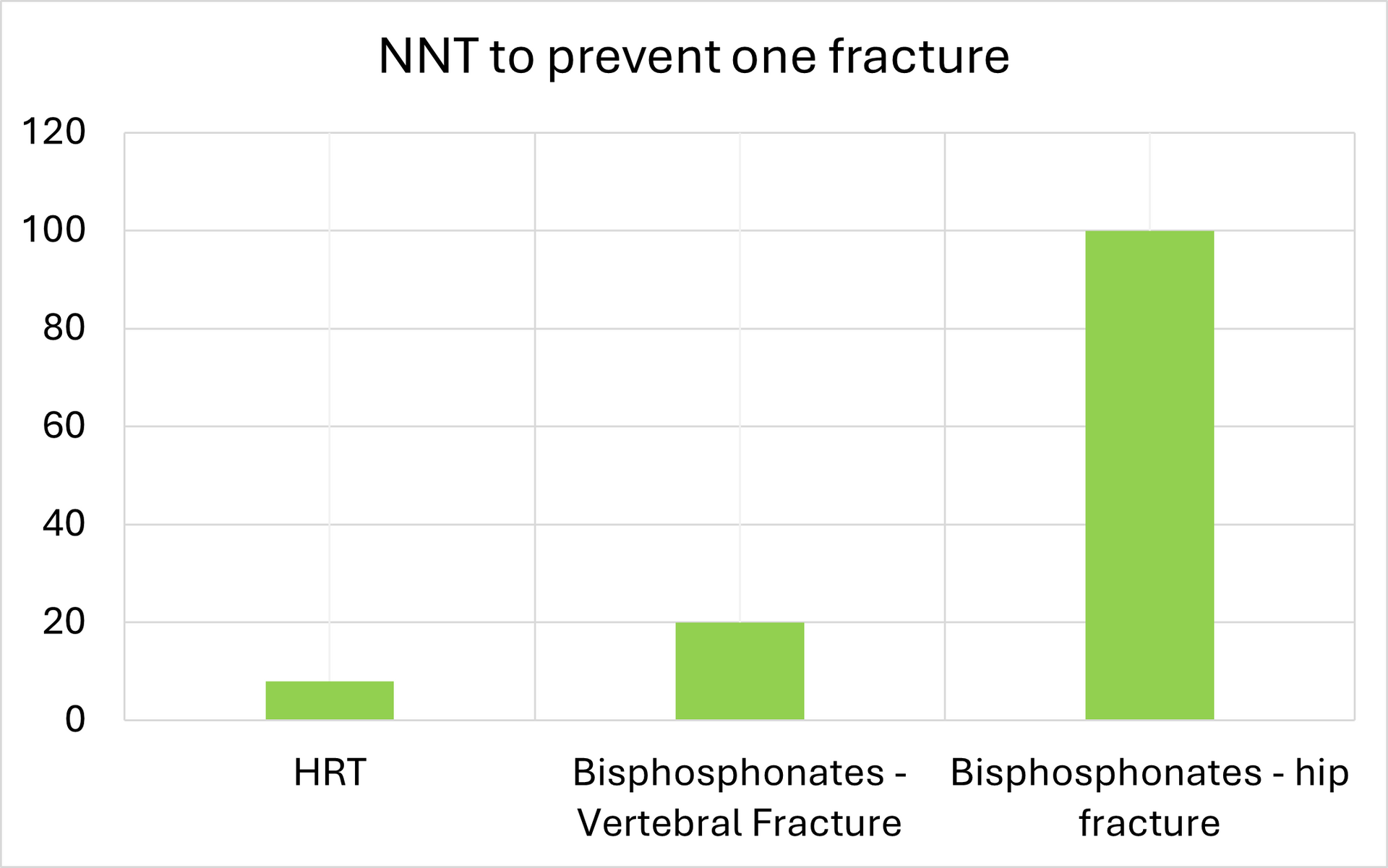

NNT and Bone Health

Both Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) and bisphosphonates are employed to reduce fracture risk in postmenopausal women, but their effectiveness varies based on individual risk factors and the type of fracture.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) at or after menopause

HRT replaces a woman’s natural estrogen that is lost when the ovaries stop producing the hormone at the time of menopause which on average is around the age of 50. It is well-established that bone mass reduces as a result of menopause and the risk of fragility fractures increases.

NNT: Approximately 8 postmenopausal women need to undergo HRT to prevent one fracture.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are a class of drugs that prevent the loss of bone density but do little to improve bone toughness. Their effectiveness in fracture prevention varies:

Vertebral Fractures: NNT: Approximately 20 women need to be treated to prevent one vertebral fracture.

Hip Fractures: NNT: Approximately 100 women need to be treated to prevent one hip fracture.

Here is a chart showing the difference between the NNT to prevent one fracture if a woman uses HRT or bisphosphonates:

Anabolic agents

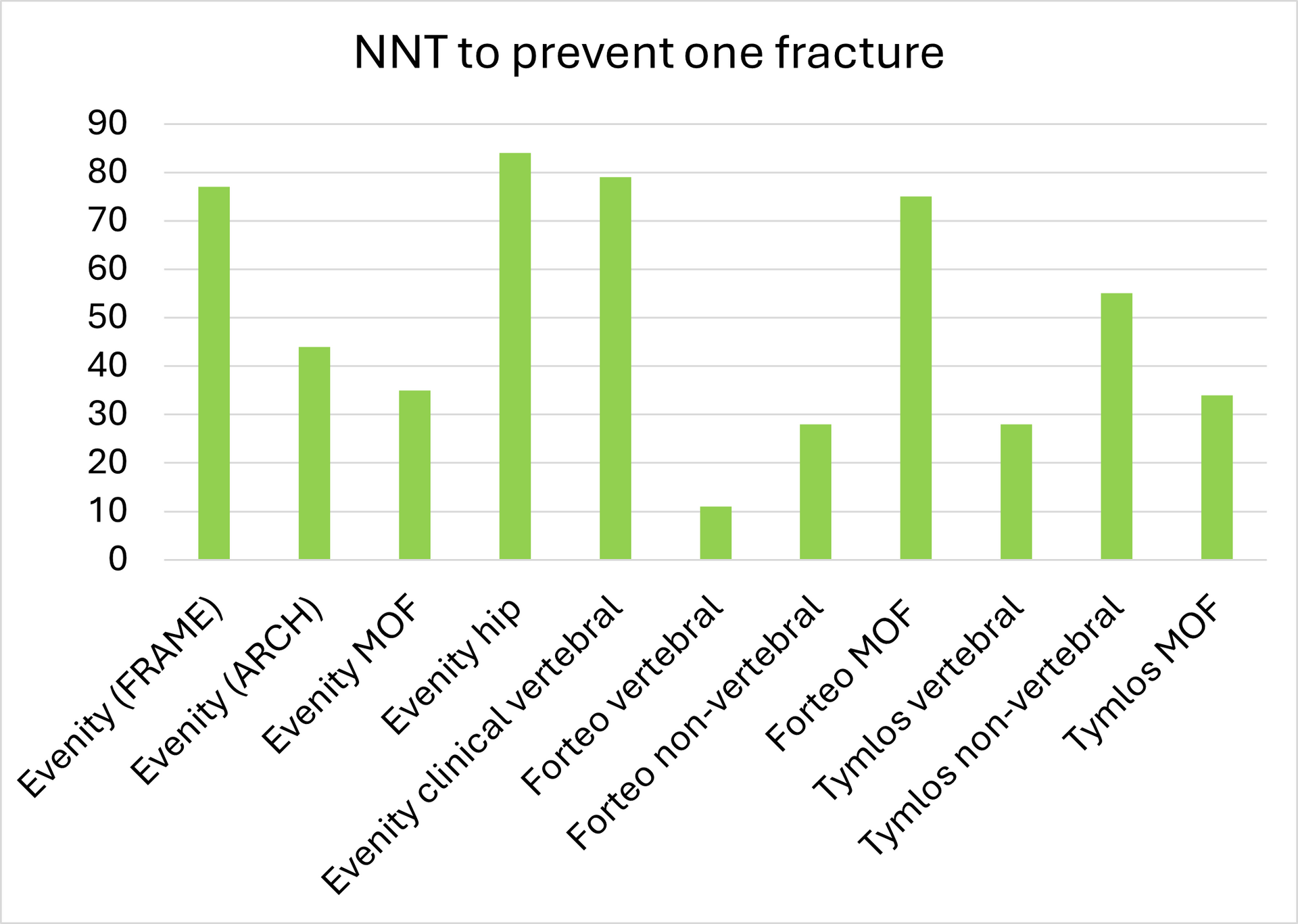

The bone building drugs (“anabolic” agents) increase bone density and bone toughness. The three in common use are: Romosozumab (Evenity), Teriparatide (Forteo) and Abaloparatide (Tymlos).

Treatment Fracture Type NNT (Approximate) / Comparator

Romosozumab Vertebral (FRAME trial) 77 Placebo

Vertebral (ARCH trial) 44 Alendronate

Major osteoporotic (MOF) 35 Alendronate

Hip 84 Alendronate

Clinical vertebral 79 Alendronate

Teriparatide Vertebral 11 Placebo

Non-vertebral 28 Placebo

Major osteoporotic 75 Placebo

Abaloparatide Vertebral 28 Placebo

Non-vertebral 55 Placebo

Major osteoporotic 34 Placebo

Here is a graphical representation of these numbers:

We hope you have enjoyed our series on databases and statistics. We did our best to keep each blog fun and educational.

Remember the wise words of Yoda, “A dark place we find ourselves, and a little more knowledge lights our way.” Allow the knowledge you have gained to illuminate your path forward on your bone health journey.

Remember, you are more than your T-Score. You are an entire wonderful you!